Digital Studies of The Holocaust

This collaborative research project aims to introduce the process of data analysis to Holocaust studies to create new ways of seeing and remembering the Holocaust.

“Race Pollution” – 1938

Nils H. Roemer, Director, Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies

Katie Fisher, Research Assistant, Belofsky Fellow

Sarthak Khanna, Information Technology Management

Angie Simmons, Research Assistant, Belofsky Fellow

Siddhant Somani, Business Analytics

The complicated relationship between racial definitions and nationalism began during the interwar years and provides an important context in attempting to understand the Nazi fixation on racial purity. Following the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, the quest for national identities emerged throughout Europe as newly formed nations coalesced from lands formerly governed by empires. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson’s concept of national self-determination encouraged the formation of nations based on people groups.

As a result, discriminatory attitudes and programs began to arise against those who upset the homogeneity these new nations worked to create. In September of 1935, Nazi Germany passed two laws collectively known as the Nuremberg Laws—the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor. Both reflect the racial theories of Nazi ideology and intentionally discriminate against Jews. These laws aimed at stripping Jews of their rights as citizens and worked to establish a racial definition of Jewishness. The second law in particular banned marriage and relationships between Jews and non-Jewish Germans, deeming these forbidden unions to be “race defilement.” These laws emphasized the importance placed by the Nazis on racial purity among Germans. The laws criminalized the unions of many who had until that point considered themselves as Germans and legally married.

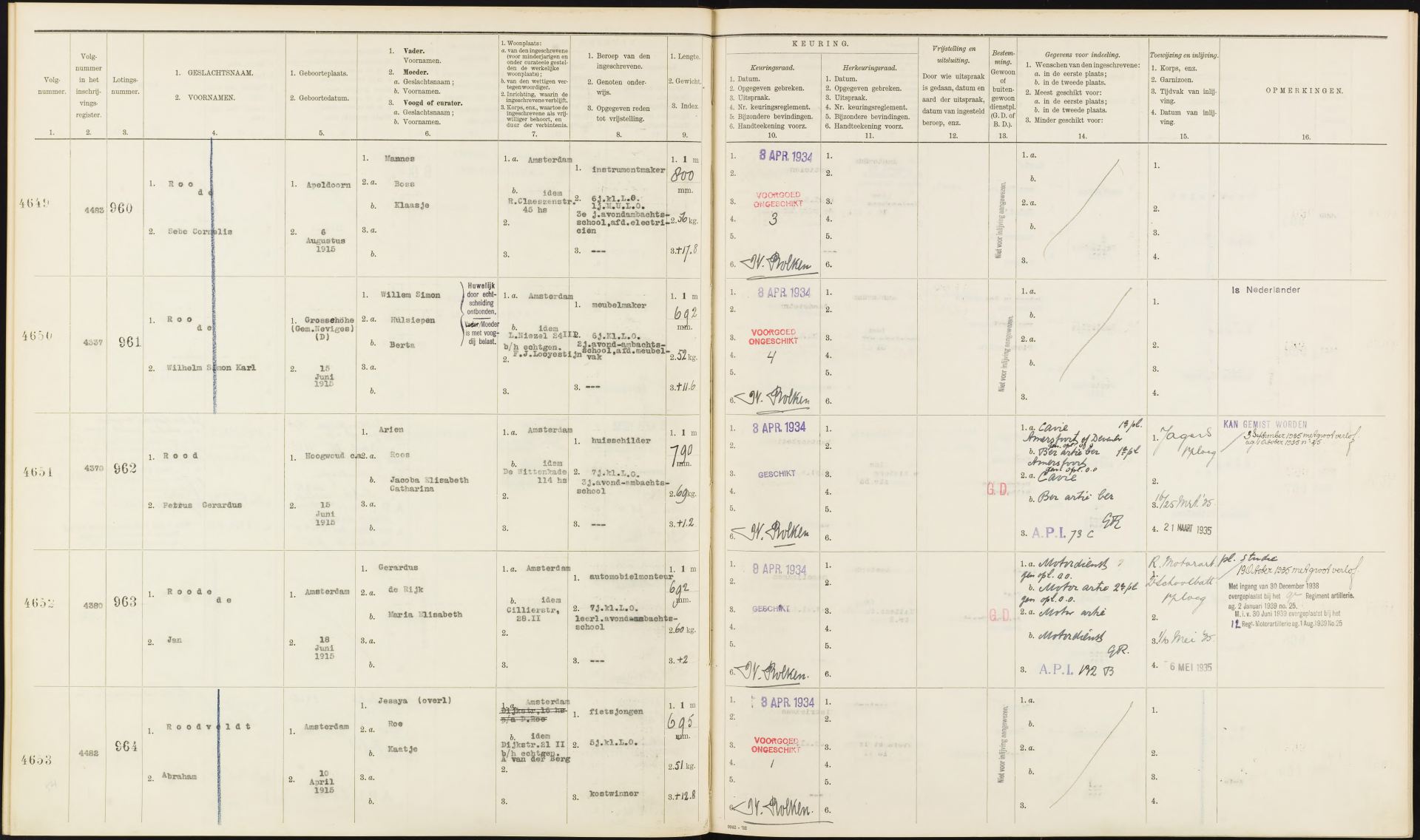

Offenders of “racial purity” laws were often subjected to public humiliation and paraded in the streets wearing a sign indicating their crime. Humiliation was a tactic employed not only in the punishment of race defilement, however, but also in the Anschluss (Nazi annexation of Austria) and Kristallnacht (November pogrom against Jews), which also took place in 1938. As shown in the data taken from the Dachau Concentration Camp prisoner intake log, the two months with the highest number of people arriving to Daucha as “rassenschander,” or those guilty of “race defilement,” were April, which followed shortly after the Anschluss in March of 1938, and September, shortly before Kristallnacht in November of that year. This would suggest that “race defilement” arrests may have been made as part of larger programs targeting Jews during those particular times of the year.

Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor of September 15, 1935

(Translated from Reichsgesetzblatt I, 1935, pp. 1146-7.)

Moved by the understanding that purity of German blood is the essential condition for the continued existence of the German people, and inspired by the inflexible determination to ensure the existence of the German nation for all time, the Reichstag has unanimously adopted the following law, which is promulgated herewith:

Article 1

1. Marriages between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden. Marriages nevertheless concluded are invalid, even if concluded abroad to circumvent this law.

2. Annulment proceedings can be initiated only by the state prosecutor.

Article 2

Extramarital relations between Jews and citizens of German or related blood are forbidden.

Article 3

Jews may not employ in their households female subjects of the state of Germany or related blood who are under 45 years old.

Article 4

1. Jews are forbidden to fly the Reich or national flag or display Reich colors.

2. They are, on the other hand, permitted to display the Jewish colors. The exercise of this right is protected by the state.

Article 5

1. Any person who violates the prohibition under Article 1 will be punished with a prison sentence with hard labor.

2. A male who violates the prohibition under Article 2 will be punished with a jail term or a prison sentence with hard labor.

3. Any person violating the provisions under Articles 3 or 4 will be punished with a jail term of up to one year and a fine, or with one or the other of these penalties.

Article 6

The Reich Minister of the Interior, in coordination with the Deputy of the Führer and the Reich Minister of Justice, will issue the legal and administrative regulations required to implement and complete this law.

Article 7

The law takes effect on the day following promulgation, except for Article 3, which goes into force on January 1, 1936.

Nuremberg, September 15, 1935

At the Reich Party Congress of Freedom

Though humiliation was often utilized in the punishment of rassenschander, many offenders were taken to concentration camps like Dachau. It is interesting to note that, though many of those taken to Dachau in 1938 for other reasons, such as those detained following the November Pogrom, were eventually released after a period of weeks or months, those who were taken for the crime of rassenschander were not released, but instead moved to other camps where they were eventually killed. This reinforces the idea that Nazis saw the crime of race defilement as a very serious crime.

Germany, 1920. Stereotypical Antisemitic images of a Jew and an “Aryan”. Photo of print from the archives of the Yad Vashem Museum, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.

Still frame from archival footage showing the public humiliation for violation of racial laws in Silesia, 1941. Accessed at United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Instytut Slaski w Opolu.

The newly formed concept of national identity based on racial homogeneity can be seen in the formation of the Nuremberg Race laws and the Nazi development of what it meant to be “German.” Geography plays a key role in understanding the data in these visualizations. The victims found in this data set were all born prior to World War I and in locations spread out all across central Europe. The Treaty of Versailles drew new country lines and national identities around them. Further, the map shown in this visualization represents contemporary country boundaries and not the boards as they were in 1938. In many cases, the borders in 1938 were very different than they had been even when these victims were born. People arrested and charged with “race defilement” may have been recorded as being German upon their arrests but this may have been a very new classification to them, and perhaps, one they would not have identified as for themselves.

View All Case Studies

The Digital Studies Team continues to build out new reports and case studies—adding to this digital library of interactive reports.

© 2020-present Ackerman Center for Holocaust Studies. All rights reserved.